Stochastic Evolution of River Valleys using Monte Carlo and Cellular Automata

Jyoti Aneja, Robert Lemiesz, Michael Di Mare

Abstract

In this project, a simple cellular automata model was built to simulate the flow of water in river-valley systems. In addition, this work explored a number of different terrain generation algorithms and compared the results visually and through comparing the behavior within the cellular automata model, namely the magnitude and timescale of the transient. Finally, several visualization techniques were considered to explore the time evolution of the system.

Introduction

Cellular automata is a useful modeling framework. It commonly finds use in approximating particle system behavior in systems such as lattice networks and biological microstructures. In general, cellular automata is used for deterministic models of simple systems but can be expanded to model more complicated, even probabilistic, systems. Cellular automata's usefulness comes from it seamless application to both fundamentally abstract and heavily applied models.

Cellular automata is a set of rules applied to a simple tiled space. Classically, square tiles in a two dimensional space are considered, forming a grid with a value associated to each square or cell. The content of the rules can vary dramatically, allowing for tunable behavior. However, usually the rules determine the value of a cell based on the values of the nearest neighbors and second nearest neighbors. The model proceeds in steps and the calculations for the next step are completed before any changes are applied. In this way, each square acts without knowledge of how its neighbors will change or how they will react.

As one would expect, the behavior of a cellular automata is heavily dependent on the governing rules. The archetypal rule set is that of Conan's Game of Life, a cellular automata system developed as a recreational demonstration of the framework. In this rule set, squares can only have two values. A square is spin up if it is surrounded by two or three spin up squares, and is spin down otherwise. Despite the simplicity of these rules, this simulation exhibits interesting and physically suggestive properties. In particular, the system tends to oscillate between seemingly random and relatively ordered structures. In addition, there are square configurations, known as “gliders” which have an associated direction of propagation and appear to “move” by inducing flips to spin up in front of the glider and flips to spin down in the tail.

Cellular automata was originally conceived in 1940 by Stanislaw Ulam during a study of the growth of crystals. Though it was conceived as an abstract model with unphysical constraints, the correct physical behavior was observed and so it proved to be a useful tool. Since then it has been applied to model, to limited effect, the propagation of wave fronts and neural networks, among other systems.

In addition to more practical pursuits, cellular automata has received attention as a point of philosophical debate. James Crutchfield, now a physics professor at the University of California, once rigorously proved that cellular automata models could exhibit statistically significant particle behavior and used this theory to postulate that the standard model could be a statistical description of a fundamentally cellular automata universe. Simultaneously, Stephen Wolfram, now the CEO of Wolfram Research, once posited that the spontaneous generation of order observed in cellular automata systems were an indication of the potential for negative entropy in a physical system.

Our Work

This project was an attempt to successfully apply cellular automata to river-valley system physics. The primary objective was to observe accurate physical behavior while implementing only abstract system constraints. This implementation focused different algorithms for terrain initialization. The properties of the different terrains were analyzed visually for slope and smoothness as well as the way in which the cellular automata model behaved within the system, particularly the timescale of the transient.

Terrain Generation

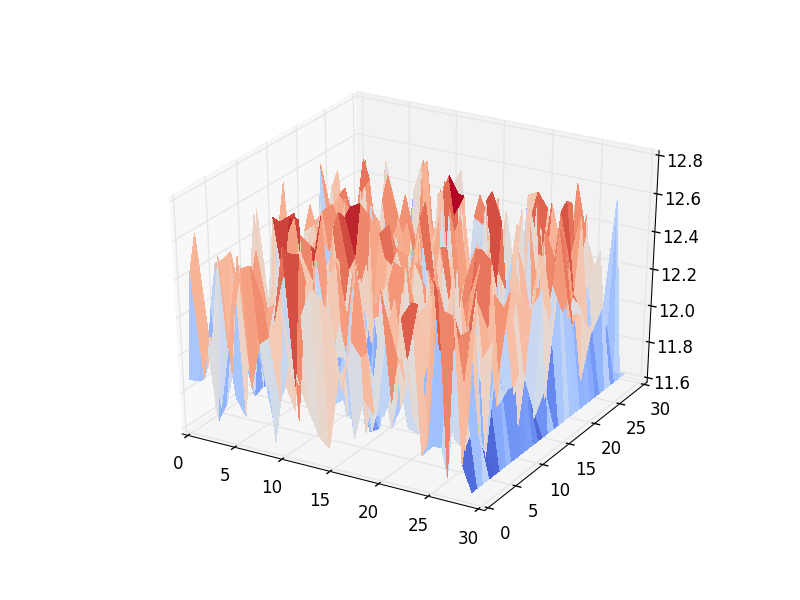

Random Heights

The most trivial and naive initialization for a two dimensional terrain is a collection of random heights. Though incredibly fast, and easy to implement and scale, the terrain suffered, as one would expect, from extremely high local slopes. This aspect was quickly improved by building the array of random heights in sequence and choosing the each consecutive height to be selected by guassian with a tunable standard deviation centered at the previous height. This implementation, has another, more severe, problem which is the intrinsic anisotropy. The desired array is two dimensional, however, the algorithm can only progress linearly thorugh a single dimension at a time. Therefore, the results were smooth and desirable in one orientation, but suffered the same high local slopes in the orthogonal direction.

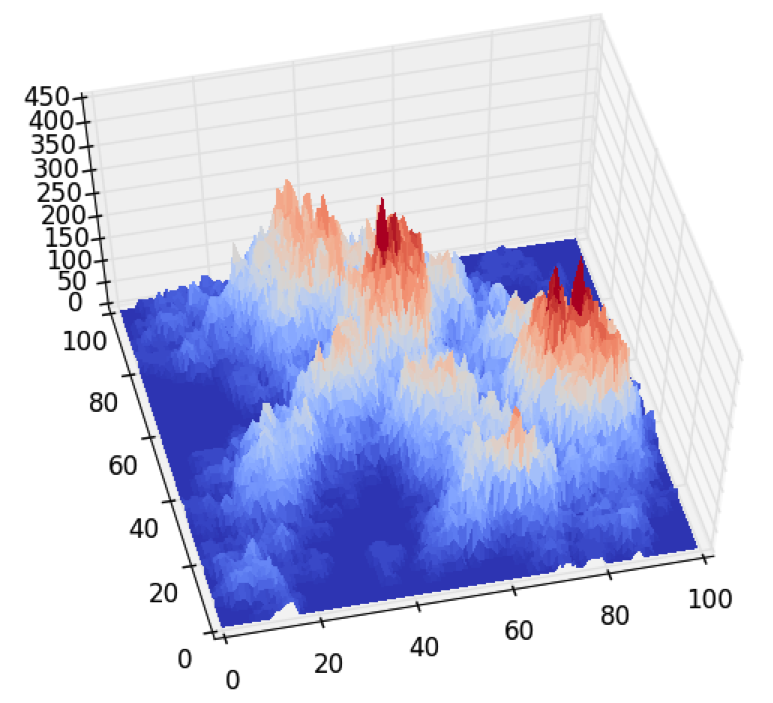

Random Generated Hills

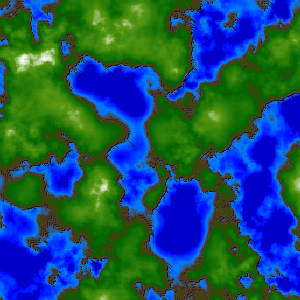

The next logical improvement on the random heights algorithm was to control the slopes of the terrain by imposing a controllable number of local maxima, called hills. For this implementation the number, height, and radius of the local maxima were chosen randomly within a tunable range. These hills were then randomly placed within the system and overlapping regions of hills were treated additively, to create the unique terrain properties. This technique offered significant improvements over the random heights algorithm. Namely there was dramatic improvement in the isotropy and smoothness of the generated terrains. This follows as expected from the isotropic constraints on the hill generations and the forced continuity of slope determined by the width and height of each hill.The primary concern with using this algorithm was the relatively consistent form of the terrains generated. While consistency is good for checking the stability of the code, it also indicated that the technique may not be ergodic which was of philosophical concern.

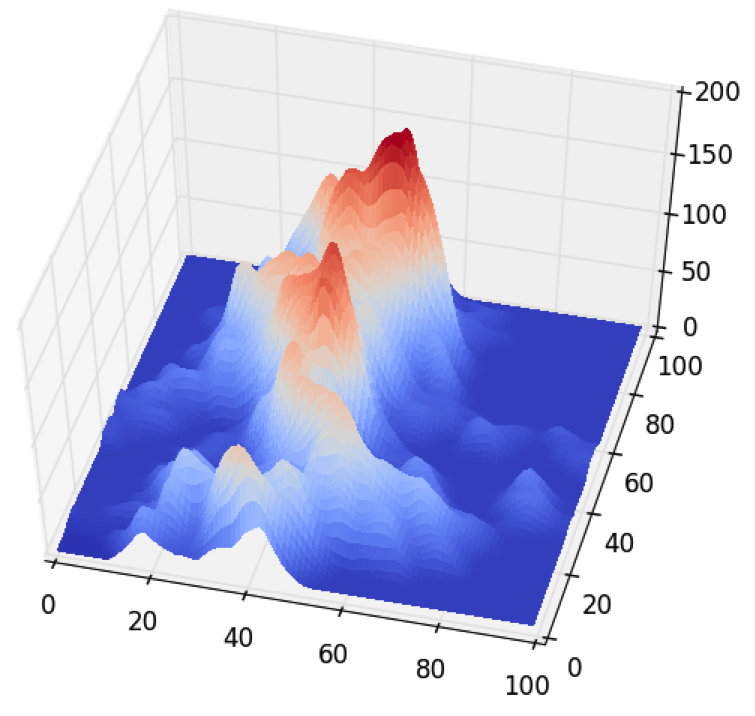

Monte Carlo Terrain

The goal of this algorithm was to draw upon inspiration from class to create a more sophisticated terrain generation code using monte carlo. This was implemented by considering the terrain generation as an arbitrarily long series of steps. In each step the algorithm randomly chooses a square to propose a height increase to. It then assess a probability of accepting that proposal based on the current height of the square and the height of the nearest neighbors.

This algorithm was then improved by implementing cluster building into the monte carlo. Instead of choosing a single square to add height to, the algorithm randomly chooses an initial square as a seed for a cluster and then recursively adds neighboring squares into the cluster with a tunable probability. This probability did not consider the square heights when deciding how to build the clusters, which makes the program intrinsically different than those covered in class. This decision was made because it yielded visually improved terrain.

The cluster build probability could be varied to dramatically change the cluster length. The probability chosen for the final simulation yielded an average cluster length of 33 units. The algorithm would then choose whether or not to increase the height of the cluster by averaging the probability contributions of each square. By utilizing clusters, the algorithm experienced an observed but unmeasured speed up as well as a number of qualitative improvements. The cluster algorithm led to broader mountains in the terrains with more natural slopes.

This algorithm has three tunable properties to change the form of the terrain constructed; two probability parameters: square height and adjacent height, and the cluster build probability. As mentioned above, the cluster build probability had a dramatic effect on the nature of the terrain. However, it also had a critical instability threshold, above which point the clusters would be so large that the algorithm would crash due to a recursive limit. This limitation appears to be intrinsic to python and could be avoided by changing languages, potentially improving the algorithm overall. Due to time constraints, this theory was not tested. Within this program, the cluster build probability was maximized using trial and error which was assumed would yield the best generated terrain.

This leaves the user with two adjustable parameters which control the probability of a cluster being increased in height during each step. The acceptance probability is given by

Paccept = min{1, is (p1 hc )/(n s) + Sum over nearest neighbrs(p2 hn )/(n s)}.

Where p1, p2 = Tunable parameters, hc = height of the current cell, hn = height of the neighboring cell, n = number of cells, s = step size

The stability limits of these parameters were explored. Unstable terrains were characterized by having nearly vertical peaks, or excessively large plateaus. The presence of vertical peaks is indicative of the probabilities of accepting clusters is suppressed except when the cluster contains mostly heights near the maximum. This causes the clusters generated in the first few steps to be the only ones capable of growing in the later steps. The presence of plateaus which span the space indicates that probability of accepting increases is too significantly influenced by the adjacent cell heights. In this way, any local maxima increase in radius until they span the space. Finally, despite these efforts, the generated terrain suffered from some degree of high local slopes leading to visual jaggedness of the terrain. The scale of these inclines was far below that of the other methods and so a simple loop was implemented to average neighboring points. This created a progressively smoother surface while maintaining the general qualities of the monte carlo terrain generation.Terrain Generation from Height Maps

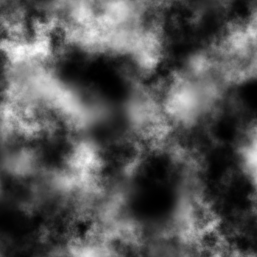

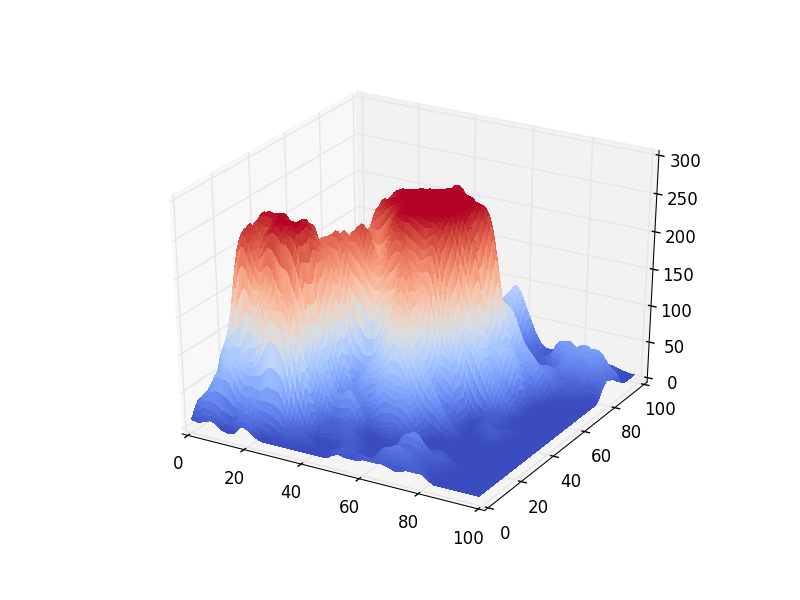

To better understand the functionality of the celluar automata model as well as compare the behavior of the randomly generated terrains to that of natural landscapes. This project also explored techniques to convert two dimensional site maps into terrain height arrays. Site maps are a common way of representing the topography of landscape. One representation of a site map is one that relates vertical height to white intensity on a black background.

In this project, two dimensional height arrays were formed from these site maps for use in the simulation. This was done by decomposing the intensity image into an appropriately sized square grid and assigning a height value to each cell based on the brightness. In this way, natural landscapes could be approximately converted into initial conditions for the simulation.

Water Flow Modeling

Before the simulation could be started, water needed to be added. Because of the nature of water and the expected fluidity of its motion, careful initialization of the water was not considered a high priority. For this reason two random initialization conditions were considered. The first was to randomly distribute water in all of the cells with equal probability. The second was to randomly distribute water in cells above a certain height threshold. This was designed to simulate an initial condition of water in ice caps on the top of the mountains. This initialization was preferred to the completely random one because it allowed for a more immediately intuitive understanding of the water flow behavior in the system.

Once the terrain was properly initialized, the next step was to create the rule system by which the cellular automata simulation would be governed. To do this, we implemented two rules. The first was that each cell would determine its new water height based off of a factor of the difference between it's total height and that of its neighbors. This would allow the water to flow down slopes with each step. The second was to change the terrain heights based on a factor of the change in water height associated with each step. This rule was designed to simulate the erosion of land under intense changes of water height.

Initially, many additional features were planned for this project, including a study of variable rain and natural springs as a water sources, water sinks at boundaries, and variable erosion rate to simulate solubility of rock layers. However, due to time constraints these plans were cut to increase focus on the primary interests in terrain generation algorithms and visualization techniques.

Conclusion and Future Steps

This project attempted an implementation of monte carlo terrain generation to create an improved cellular automata simulation of a river valley system. The goal was to observe the correct physical behavior while only implementing abstract system constraints.Four different terrain generation algorithms were considered, including monte carlo and real site map integration. A number of visualization techniques were considered and implemented with a variety of effects. Ultimately, the cellular automata simulation was observed to have the correct physical behavior and so the project was consider a success.